You’ll have heard the mantra ‘95% of worms on your farm are on pasture’. Learn about the drivers of worm challenge on your pastures so you can reduce worm intake by susceptible stock.

Where do the larvae live?

The vast majority of your total worm population (85 to 95%!) lives on pasture – as L3 larvae.

The rest are:

- In the soil – a few larvae and eggs.

- In dung pats – eggs and developing larvae.

- Inside your animals – as juvenile worms, adults and eggs.

Think of your farm as a worm iceberg. Killing worms at the very top (inside your animals) is part of controlling them. But if you don’t include the rest of the iceberg in your management plan, you’ll never progress.

Ground zero

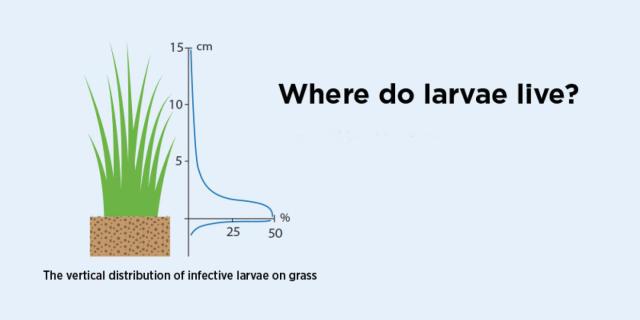

The top 1–2cm of your soil is a part of the worm iceberg.

Next level

- The lower sward (bottom 2.5 cm of your pasture) makes up much of the rest of the worm iceberg, especially in sheep-grazed pasture.

- For cattle-grazed pasture the lower sward is ‘the bottom 1/3rd of the pasture’.

- More L3 larvae like to live in the lower sward if pasture forms a dense mat (think browntop)

- There are relatively fewer larvae where the sward is more open (short rotation grasses and forage crops).

- Bare ground is barely hospitable at all!

Keep your animals’ mouths out of the lower sward, and you’ll win three ways:

- They’ll be better fed overall (this is #1!).

- They’ll take in less L3’s.

- You’ll be keeping them away from that larvae-infested soil as well.

Top floor

The top 2/3rds of the pasture is the safest grazing zone, where your susceptible animals are least likely to ingest larvae with their grass.

Larvae are more likely to be active in the upper sward under warm conditions when there are plenty of moisture droplets on the leaves for them to move upwards.

They’ll move further down as conditions dry out, so they can remain in a moisture film.

Want to really minimise the risk of your animals getting infected by worms? Graze forages with wide leaves and an open growth habit. Examples are chicory, clovers, plantain and brassicas. New Zealand research has shown these can carry fewer larvae than grass. Plus they’re often more nourishing, meaning young animals grow out faster, requiring less drench inputs as they reach a mature size earlier.

Short term crops that are grazed down to open ground and re-sown in another forage (+/- cultivation), give an extra opportunity to knock back larvae though the re-sowing process, where there is no/minimal vegetation for larvae to survive on. Cultivation can further disrupt larvae in the soil layer.

It’s not a given though that these forages will always be completely worm-free, especially if there are extensive grass edges around them. Monitoring is critical to double-check that parasite challenge is indeed low.

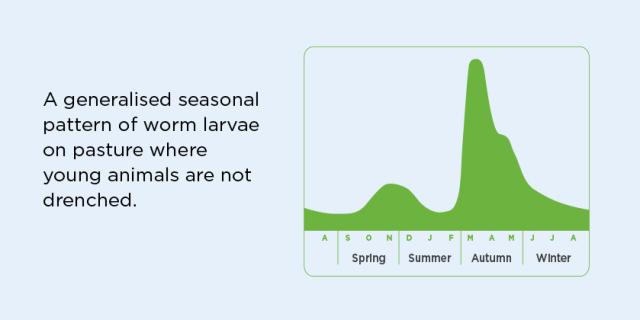

Seasonal patterns of worm larvae on pasture

Sheep

Lambing ewes can lose some of their immunity to worms. Their faecal egg counts may rise prior to lambing and will often have dropped back to normal by docking, certainly by weaning. Young ewes, ewes carrying multiples and fine wool breeds tend to be more affected. Teladorsagia is the predominant worm at this time. See our article on understanding parasite pressure in ewes over lambing for more information. The initial spring rise in worm larvae comes partly from ewes, but also from larvae laid down by lambs the previous autumn. Young lambs have no immunity to worms. Once they have adult egg-laying worms on board, they are the biggest contributors to larvae on pasture.

Cattle

Calves ingest larvae that survived on the pasture over winter. As calves start eating grass they take in larvae, these mature to egg laying adults. The eggs hatch and kick off a spring rise in pasture contamination. This is likely to be more pronounced in systems running artificially reared calves, compared to cow/calf systems.

Sheep

In wet summers the spring peak of larvae on pasture continues to build, fuelled by egg output from lambs. In very dry conditions there may be a big drop in larval numbers on pasture. Barbers Pole worm thrives in the hotter conditions of summer. In wet summers, Trichostrongylus may predominate as summer progresses.

Cattle

In wet summers the spring peak of larvae on pasture continues to build, fuelled by egg output from calves. In very dry conditions there may be a big drop in larval numbers on pasture. Early summer is a common time to see outbreaks of lungworm in calves. Cooperia is the most common worm in calves in their first summer.

Sheep

Larval numbers on pasture are highest in the autumn, via the multiplication of worms from lambs since spring. Autumn rains after a long dry period enable larvae to migrate out of the soil layer and contaminate the short grass that starts to grow. Over-grazing short pastures at this time with susceptible stock can result in big worm problems with further contamination of pasture through into the winter. Trichostrongylus becomes the most predominant worm in autumn.

Cattle

Larval numbers on pasture are high in the autumn, via the multiplication of worms from calves since spring. Autumn rains after a long dry period enable larvae to migrate out of the soil layer and contaminate the short grass that starts to grow. Over-grazing short pastures at this time with susceptible stock can result in big worm problems with further contamination of pasture through into the winter. Ostertagia and Cooperia predominate in autumn.

Sheep

Larval numbers on pasture drop off over winter as lower temperatures reduce the development rate of larval stages on pasture. Lambs are gaining immunity to worms and contribute less eggs to pasture. However, a high pasture larval burden created in autumn can continue to cause problems in winter, especially where stock are underfed.

Cattle

A high pasture larval burden created in autumn can continue to challenge calves in winter, especially if they are underfed. However larval numbers on pasture do drop off over winter. Lower temperatures reduce the development rate of larval stages on pasture and calves are gaining immunity to worms and contribute less eggs back onto pasture.