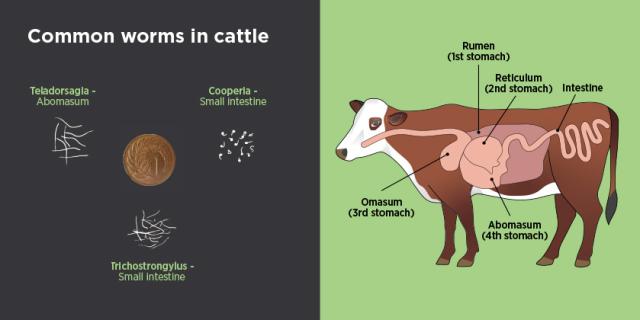

Meet your enemies! Learn about the important worm species of cattle – effects on the animal, seasonal pattern, diagnosis, treatment and prevention strategies.

What you see

In severely affected immature calves, look for classic signs of parasitism - weight loss, profuse scouring, dullness. Cattle 18 months-plus are more likely to show depressed growth rates. But when these older cattle are under enough feed stress, they can show more severe disease too.

Type I Ostertagiosis: Most commonly seen in calves from summer through to winter. Scouring and weight loss is caused by increasing numbers of adult and immature worms in the stomach. This can thicken the stomach wall and alter the stomach pH, interfering with digestion and causing diarrhoea. Calves with Ostertagia may not have very high faecal egg counts; it is not a prolific egg-layer.

Type II Ostertagiosis: Occurs when ‘inhibited’ L4 larvae, which have been sitting dormant in the stomach wall break out en-masse, severely damaging the stomach lining. Affected animals sicken quickly and sometimes die. Type II Ostertagiasis occurs mostly in 12-20 month cattle. Outbreaks can occur when cattle transition from tight winter feeding onto better spring feed. It can also be seen in mature cows after prolonged feed stress. Thankfully, Type II Ostertagiasis is relatively rare.

Life cycle

Larvae on pasture are eaten by calves in spring. By late summer, even more larvae can be present, reinfecting calves. Worms mature to adults and live in the abomasum.

Over-wintering: Lower temperatures slow larval maturity on pasture, but the life cycle continues through the cooler months. Some viable eggs can survive for long a long time inside undisturbed dung pats. Ostertagia can develop under cooler conditions than some other worm species, and its life cycle can kick off earlier the spring as a result.

Ostertagia survives across the range of NZ environments.

Most at risk

Calves, especially from late summer to early winter. Early infections in spring build summer larval numbers on pasture and calves become re-infected with increasing numbers of Type I Ostertagia into autumn and winter.

As calves mature to 12 to18 months old, they start to develop resistance to Ostertagia.

Stressed and/or underfed older cattle in late winter and spring can be at risk of Type II Ostertagia mass eruptions from the stomach wall.

Post-mortem

The lining of the abomasum can appear thickened, contain excess fluid, and may look pock-marked, with grey raised nodules. Adults are 6-9mm long so unless your close-up vision is super-sharp and the animal is very freshly dead you may not see them. A hand lens can help.

Treatment

Calves/R1’s: Good nutrition, plenty of low worm contamination feed and adequate drench inputs. Monitor drench efficacy!

Older cattle: Good feeding and management is key; well-fed older cattle free of other health challenges rarely succumb to Ostertagia. Make dietary changes slowly.

Strategic drench treatments for R2 and adult cattle can sometimes be a good preventive measure; common treatment times would be pre-winter and/or end of winter. Individual cattle growing well may not need drenching. Instead, treat only those not reaching target growth rates or body condition scores, and leave the best performers untreated.

Macrocyclic lactone (also known as ML or mectin) drenches are particularly effective at removing inhibited larvae. Injections are a good choice for R2 and older cattle. Calves/R1’s should be treated orally with combination drenches containing ML drench. Oral ML’s perform better against resistant Cooperia while still giving good Ostertagia control.

As most young cattle are drenched with the ML family at the start of winter, and often again at the end, Type II Ostertagiosis is rare today.

What you see

Cooperia live in the small intestine. Heavy Cooperia burdens cause weight loss, scouring and even deaths in calves, though each individual worm is not as nasty as Ostertagia. Many more Cooperia are needed to create the same level of disease. FECs in sick calves may exceed 2,000+ eggs per gram.

Cooperia is a common cause of poor performance in New Zealand calves. Cooperia oncophora has developed almost complete resistance to the ML drench family. If you drench calves with single active injections or pour-on’s, many Cooperia can survive and make calves sick. Cooperia is also starting to show resistance to combination drenches; don’t presume drenched calves are safe from infection. Test your drench!

Life cycle

Cooperia can lay many eggs and larvae can build up quickly on pasture. Cooperia needs higher temperatures than Ostertagia to develop and are usually most troublesome in calves from late spring through to autumn.

Most at risk

Calves, especially artificially reared animals, intensively grazed in systems dominated by young cattle. As calves reach 12 months, they start to develop some resistance to Cooperia and faecal egg counts start to fall.

The bigger and better-grown your calves, the faster they become immune. Very good calves shrug off Cooperia by 6–9 months while poorly grown, stressed calves may still be susceptible at 12–15 months.

Post-mortem

Coiled worms 10-15mm long may be seen close to the wall of the small intestine. A hand lens helps to see them. In bad cases intestines may appear reddened, with excess fluid content.

Prevention

Calves/R1’s: Good nutrition, plenty of low worm contamination feed and adequate drench inputs (per your farm system). Monitor drench efficacy!

Spell pastures to reduce worm larval burdens; cross graze with other animals or adult cattle and feed crop or new pasture – these all help reduce your calves’ Cooperia challenge.

Trichostrongylus axei, also known as Stomach hair worms (T. axei) can infect cattle, horses and sheep. Two other species of Trichostrongylus live in the small intestine. They are mostly a minor part of cattle worm burdens.

What you see

T. axei can dominate outbreaks of clinical parasitism in autumn calves, and in R1’s later in winter and into the following spring. Look for reduced appetite, weight loss and scouring.

Life cycle

Similar to other common cattle gut worms. Eggs take at least 5 days to hatch and develop to the infective L3 stage, often longer. From ingestion of L3 larvae to egg laying adults in the gut takes around 3 weeks.

This worm tends to be a ‘late bloomer’ in cattle systems, typically peaking on pasture and challenging yearling to 18 month old cattle in their second spring. Like Ostertagia it tolerates cool conditions and can survive frosts.

Most at risk

Older calves and yearlings, autumn-born calves. T. axei larvae may peak on pasture as late as October. Undergrown young cattle may not develop strong resistance to this worm until 18-20 months.

Post-mortem

‘Thumb-print’ swellings, redness and excess fluid in lining of abomasum.

Prevention

Calves/R1’s: Good nutrition plenty of low worm contamination feed and adequate drench inputs (per your farm system). Monitor drench efficacy!

Spelling pastures to reduce worm larval burdens; cross graze with other animals or adult cattle, and feed crop or new pasture – these all help reduce your calves’ T. axei challenge.

For information on lungworm and liver fluke, please see: Tapeworm liver fluke and lungworm.