Meet your enemies! Learn about the important worm species of sheep – effects on the animal, seasonal pattern, diagnosis, treatment and prevention strategies.

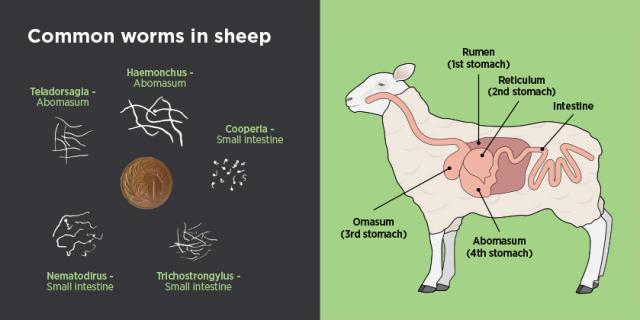

Inside the animal

Sheep worms most often live in the abomasum (4th stomach) and the small intestine. Some worms can exist in both. Sheep almost always carry a mix of worm species.

Where and how bad?

Most worm species are found throughout New Zealand – with some regional differences.

For example, Haemonchus (Barber’s Pole worm) is more common in the warmer, northern parts of the country. Whereas Nematodirus mostly only causes problems in the deep South – it’s eggs require winter chilling to hatch and challenge young lambs in spring.

Barber’s Pole worm and Nematodirus can cause sudden, severe illness and death – though they might not be an issue at your place, depending on location. Trichostrongylus can cause serious disease in autumn throughout NZ if not well managed. The others would typically be part of a mixed worm infection and not a cause of disease on their own.

Worm species

Where you’ll find it

(Barbers Pole worm) is prevalent for much of the year in warmer northern areas. It’s confined to summer through the middle of the country. It’s rarer in the bottom half of the South Island – but not unheard of.

What you see

This worm sucks blood from your sheep, so one sign is lambs with pale eye membranes (anaemia). Don’t check the gums – they often look pale regardess. Check out this video: Have my lambs got Barber's Pole.

Growth rates slow. Even a sub-clinical infection (where you can’t see signs of illness) can cut liveweight gain by 30%. 1000 adults in the stomach can suck 50ml of blood each day!

Pre-adult stages of Barbers Pole worm can also suck blood. This is tricky to pick up in a faecal egg count, as these ‘teenage’ worms are not shedding eggs. Animals with a zero or low egg count may already be suffering from blood loss.

Sheep may sit down more, pant, and fluid may accumulate under the lower jaw (‘bottle jaw’). Sheep can die of anaemia if left untreated. Sometimes the first sign is ‘sudden’ death.

Scouring is not common – in fact, dehydration from blood loss can cause constipation.

Life cycle

Eggs on pasture can only hatch with summer warmth and moisture. Barber’s Pole outbreaks can occur after quite minimal summer rainfall, especially if your animals are stressed from lack of feed in a drought. L3 larvae eaten by sheep take about 3 weeks to become adults in the abomasum and can be causing blood loss in this period.

Immature Barber’s Pole worm larvae can stop developing and ‘rest’ or lie dormant in the sheep’s stomach. We call these larvae ‘inhibited’. Effective drenches should clear these out.

Most at risk

Lambs, especially in late summer and autumn. Larvae on pasture can build rapidly and young sheep can’t always cope with the blood loss they cause. Older, well-fed sheep typically develop some immunity – lambs don’t have this. Disease risk drops as sheep age but two-tooths are still vulnerable. Cooler temperatures slow egg hatching and development, easing the challenge.

Older sheep that are under-fed or suffering another health issue may have low immunity and be more prone to Barber’s Pole.

Identification

There are currently two methods to identify Haemonchus in a faecal sample: GIN PCR and larval culture. GIN PCR is quicker, which can help with management and drenching decisions. PCR is quicker, which helps you decide sooner if a drench is needed for barber’s pole. On post-mortem, cut open the abomasum (on the sheep's right side, behind the liver) and immediately look down into the fluid. There will be a swirling mass of worms. Females are 20–35mm long, and stripy. Males are shorter and reddish. The odd worm here and there is not enough – if the sheep has died of Barber's Pole, you will see many worms. Look also for pin-head bleeding lesions on the lining of the abomasum.

Management

Start faecal egg counting lambs in early summer as they are getting close to their next expected drench date and watch for increases over 1,000 eggs per gram in individual FECs. FECs can rise to over 10,000 epg in bad cases. Larval cultures from FEC samples can help indicate what proportion of the worms are Barber’s Pole.

Be aware – lambs scouring with very high FECs are more likely to be suffering from Trichostrongylus. Barbers pole worm is not a major cause of scouring.

If rain follows hot dry weather, it may be prudent to treat lambs before FECs increase. Remember, immature worms can consume blood before they start laying eggs.

Moxidectin and Closantel (usually in combination with abamectin) are two drench actives that give extra protection against Barber’s Pole worm by killing incoming larvae for a number of weeks after drenching. These can be useful in situations of high challenge. Relying on these, year after year, to manage Barber’s Pole worm can increase drench resistance in other worm species. Great nutrition to ewes and provision of non-grass forages and/or cattle-grazed pasture for lambs are good management strategies for reducing Barber’s Pole challenge. Sheep with worm resistant/resilient genetics are generally better able to withstand Barber’s Pole challenge.

Two species of Nematodirus (filicollis and spathiger) live in the small intestine and in some cases cause severe disease in young lambs.

Where you’ll find it

Throughout NZ. Fillicolis require winter chilling to hatch; as conditions warm in spring they can hatch en-masse and cause disease in young lambs. This pattern of disease is mostly seen in the very south of the country. North Island Nematodirus (of whichever species) may be present in low-moderate numbers throughout the year and rarely cause disease on their own.

What you see

Sudden violent scouring, deaths in young lambs; often before weaning. This pattern of disease is only seen in the southern part of the South Island.

Life cycle

Females lay only 25 to 30 eggs per day. Eggs are large and the larvae develop right through to L3 while still within the egg, ensuring high survival.

Most at risk

Lambs in their first spring and early summer.

Identification

Large eggs make Nematodirus easy to identify in a faecal egg sample.

Prevention/treatment

FEC test lambs pre-weaning to assess the severity of Nematodirus challenge. Dead lambs can occur at FEC’s of 1000 eggs per gram. Production is lost well below this level. In severe outbreaks, immature worms kill lambs before eggs are visible in the faeces. For this reason, some farms will preventively drench pre-weaning. Oral electrolytes may help lambs that develop a sudden severe scour from Nematodirus.

Because of its prolonged survival on pasture, areas where outbreaks occur in one year may present a higher risk to lambs the following year. Lambing ewes in BCS 3+ and managing pasture so that ewes and lambs are not grazing into the bottom 2.5cm will also help.

Note!!! Another cause of sudden violent scouring (especially in artificially reared lambs) is Coccidiosis, which requires different treatment. This can be diagnosed on post-mortem and faecal samples.

There are three important worms in this family. Kiwi farmers and vets know them as ‘black scour worms’.

Stomach hair worm (T. axei) lives in the abomasum. Cattle and horses can also be infected with T axei. T axei rarely causes disease on it’s own in sheep. The other two (T. colubriformis and T. vitrinus) live in the small intestine and are more likely the cause of problems in lambs.

Where you’ll find it

Throughout NZ. Wet summers favour Trichostrongylus build-up; bad outbreaks of this worm occur the following autumn and early winter as high numbers of larvae on pasture are consumed by lambs.

Trichostrongylus larvae can survive freeze/thaw cycles, so a couple of frosts will not kill them. They can continue to challenge non-immune sheep during winter and set up a higher level of pasture larval challenge the following spring.

What you see

Lambs lose weight, scour and some may die. Infections can come as a surprise when you’ve treated lambs with long-acting drench for Barber’s Pole worm (e.g Moxidectin, Clostantel) – these products have little persistency against Trichostrongylus and lambs can become sick 3–4 weeks after a drench.

Life cycle

Adult females can lay 900-1,000 eggs per day. Having 3,000 adults in the gut is thought to be enough to cause clinical disease in lambs; in mature ewes, that figure is 10,000+.

Most at risk

Young sheep in late summer, autumn and into winter. Two-tooths are sometimes affected in autumn, especially if they are short of feed.

Identification

Larval culture is the only way to identify Trichostrongylus in a faecal sample. Lambs will have a profuse dark green/black scour. If the lamb is freshly dead, cut open the abomasum (on the animal’s right side, behind the liver) and immediately check the fluid for swirling motions caused by tiny, thread-like Trichstrongylus worms. They are 5–8mm long and there will be lots! . They can also be seen in large numbers in the first few metres of small intestine. A magnifying lens can help!

Management

Avoid lamb-only grazing of permanent pasture in autumn, especially after a wet summer. If adult sheep and cattle are the dominant grazing animals through this time, outbreaks are unlikely. Avoid rotating lambs around the same small area through the risk period.

Don’t extend drench intervals without solid monitoring and good nutrition. Use a drench you know is highly effective. Do a drench check after each treatment in late summer and autumn and be prepared to swap to a more effective drench family or quit lambs if your routine drench fails the drench check.

Teladorsagia are known as Brown stomach worms. Back in the day they were called ‘Ostertagia’, but they’ve had a name change.

Where you’ll find it

Throughout NZ, but tends to increase as you head south. Eggs will hatch and grow to L3 stage at lowish temperatures (10 degrees C) – this worm often predominates in late winter and early spring, especially in ewes pre-lamb. Teladorsagia can form a higher percentage of the worm burden for longer in cooler areas. Other worm species need warmer temperatures for development and can ‘outbreed’ Teladorsagia in warmer climates.

What you see

Lambs lose weight and can scour.

Life cycle

Teladorsagia live in the abomasum. Like cattle Ostertagia, immature larvae can embed themselves in the stomach wall and may sit in an ‘inhibited’ phase; recommencing development weeks or months later.

Adult worms don’t shed as many eggs as Barbers Pole worm or Trichostrongylus. An adult female may lay 200 eggs per day. Each worm lays fewer eggs as the number of adult worms increases, so high FECs are not always a feature. They tend to be part of mixed worm infections rather than a problem on their own.

Adult Teladorsagia are not long-lived. So if you are treating animals with an ineffective drench (especially ewes with long-acting products at lambing), resistant larvae can quickly replace a more susceptible adult population. Teladorsagia was the first sheep worm to show widespread and severe resistance to a range of drenches in New Zealand.

Most at risk

Young stock. 5,000 Teladorsagia in the abomasum are enough to cause clinical signs of parasitism in lambs. But growth rates will be suppressed well below this infection level.

Over-wintering: L3 larvae are resilient and able to survive some freeze/thaw cycles on pasture.

Identification

Larval culture is the only way to identify this worm in a faecal sample. On post-mortem, there can be visible nodules. Lambs will scour. These worms are very small and difficult to see with the naked eye.

Prevention/treatment

Good nutrition, plus use of highly effective drenches when needed will generally keep Teladorsagia in check. Avoid long-acting pre-lamb treatments for ewes – they give this parasite a head-start in late winter and early spring. Drench check your early season lamb treatments and be prepared to change to a more effective drench family if significant eggs are present in post-treatment samples.

Where you’ll find it

Throughout NZ.

What you see

Generally part of a mixed infection. In very high numbers, Cooperia can cause diarrhoea and weight loss.

Life cycle

Adult worms live in the small intestine. Cooperia have the same life cycle as other intestinal worms. Young lambs may carry infestations of cattle Cooperia – these typically drop off after the first or second lamb drench.

Most at risk

Most common in autumn and winter. Generally considered low-risk for sheep. May be the predominant parasite in ewe larval cultures in winter.

Identification

Larval culture is the only way to identify Cooperia in a faecal sample.

These worms live in the large intestine of sheep and in high numbers, cause damage and blood loss. Thankfully they are usually a minor part of the worm mix.

Infestations take a long time to build up (two months to mature). Seldom seen in lambs on a regular drenching programme. Bowel worms can contribute to winter ill thrift in ewes but are not a primary cause. Well-fed and managed ewes are rarely troubled by these parasites.

They are sensitive to most drenches. Best practice nutrition and management should ensure these worms don’t become a problem.

These tiny worms have a very different life cycle to other gut worms.

Larvae can be present in ewe’s or cow’s milk and ingested by the lamb or/calf. Strongyloides can also penetrate the skin of young animals.

In NZ, young animals typically develop immunity to this worm early in life. Lambs may show a transient scour around docking/tailing that is caused by this worm. Treatment is not usually needed.

Watch this video on lamb docking drench for further tips and advice.

For information on lungworm and liver fluke, please see: Tapeworm liver fluke and lungworm.