Tararua sheep and beef farmers Marty and Debbie Hull have given access to the public to their “magical” waterfall for the entire 20 years they have owned the farm.

The Hulls, who fatten lambs and steers on 400 hectares east of Pongaroa in the Tararua district, have welcomed waterfall enthusiasts for the entire 20 years they have owned the property.

Marty says up to 200 people a year do the 45-minute walk across his farm to see the stately Mangatiti Falls.

“They’re pretty magical… anyone who goes down there is really thrilled.”

The walk uses a farm track and starts in a parking area beside the Hulls’ woolshed, where visitors arrive by prior arrangement.

It’s a long drive just to get to that point: the village of Pongaroa – which has a pub, accommodation, store and service station – is 50 minutes’ drive south-east of Dannevirke, with the falls another 15 minutes on.

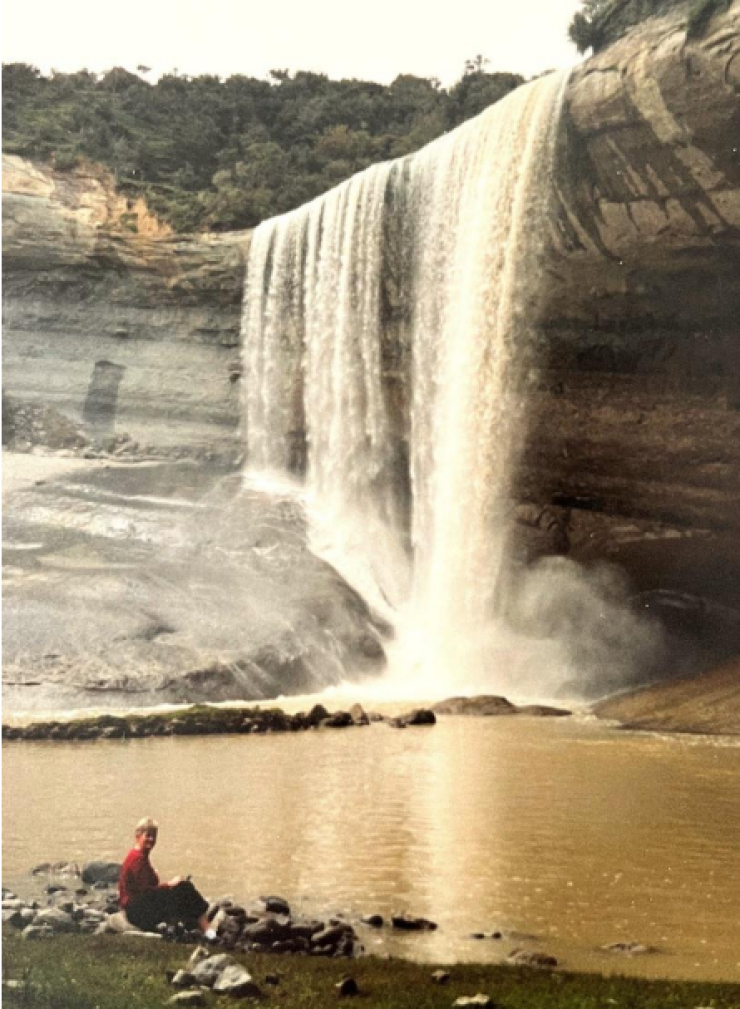

They are worth the drive, though, at around thirty metres high, covering the whole broad width of the Aohanga River, and tucked away in a fenced, 20-hectare block of mature bush.

Marty has simple, generous reasons for maintaining the previous owner’s practice of allowing anyone in to do the walk (as long as they ring first to ask).

“It’s been going on a long time, and we’ve just carried it on. They’re just sitting down there, so we might as well let people see them.”

The bush surrounding the falls has been protected by the Hulls under a Queen Elizabeth II Trust covenant. Marty says it makes for a cinematic scene.

“They’re over a hundred feet high, there’s bush on each side. There’s no other waterfall around like it, and no sort of sense of why it is there. I guess it’s just hard over soft, and millions of years. Peter Jackson could have made a film in there, put it that way.”

Marty meets all visitors, handing over a map showing the route to the falls: “You’d never find them if you didn’t get told.”

He asks visitors to sign a consent form, which includes a list of possible hazards to be aware of, such as stock and farm machinery movements.

School groups and tourists from overseas are among the visitors, he says.

“We had a hundred kids here the other day – nine little buses. And overseas people, they look on websites and see us, and they come down. A lot of people are really interested in waterfalls.”

Iwi celebrates access champions

The falls and the surrounding Tararua district are the ancestral territory of the Rangitāne o Tamaki nui-ā-Rua iwi.

Co-chair Lorraine Stephenson said the falls were quite significant for the iwi, being on a traditional walking route from around Dannevirke to the river-mouth settlement of Aohanga – some 80 kilometres away.

“That was land that our people used to travel over on a hīkoi from inland out to the coast. They used to go across the Puketoi Range and follow the Aohanga River down.”

She acknowledged farmers like the Hulls who permit public access.

“For us as Māori, access to the whenua… a lot of it was lost. So to get public access to places like the falls is something we support.”

Lorraine and her whānau have been building a new tradition of horse-trekking out to Aohanga, in the steps of their ancestors.

“For 37 years we’ve been riding to the coast from Dannevirke – it’s the fourth generation that’s riding now.”

That has given her a unique perspective on the importance of public access to the land, but also the difficulties – particularly with a recent widespread change in the area from grazing to forestry.

“Unless you know someone, to get access can be really difficult. So we’ve experienced that land access problem, but we celebrate those people who allow it.”

In her experience, farmers did not encounter problems when they allowed people access to the outdoors through their farms.

“The people who go to things like the falls are generally doing it respectfully … that’s their love, their passion.”

Thrill of sharing

Marty and Debbie have never charged access for the walk, except for a one-off occasion when they hosted a fundraiser for a community group.

“If you charge, you become responsible for health and safety and all that.”

So what’s in it for him?

“It’s just the thrill of people actually seeing it. They come back and they say, that was unbelievable.”

The practice is not without its difficulties.

“Sometimes it feels more of a hassle than it’s worth. But they always ring ahead [to arrange to come], and I make it a time that suits me, around the farming and that, so it doesn’t mess up the day.”

He has never really considered finding another way to monetise the falls, such as setting up a B&B.

“I’m just not really interested in that.”

Besides, the couple have their hands full, with 300 Romney ewes and up to seven hundred dairy-cross steers (Hereford or Angus crossed with Friesian) and Friesian bulls.

“There’s always something to do on the farm. We fatten the steers up until they’re 600 kilos live weight, which takes about two to two-and-a-half years. Then off to the works.”

The Romney lambs are also destined for the freezer.

“We put a black-face ram over the ewes, and fatten the lambs. We don’t run any hoggets, no replacements – we just buy in-lamb ewes as needed.”

They get a gang in once a year to shear any lambs that don’t make the draft, and the ewes.

“There’s no money in that, but at least nowadays you do make enough to pay for the shearing.”

Marty started off in sheep and beef when he left school, but got into dairying as a path toward farm ownership.

Does having regular visitors have any business benefits? For example, in such an isolated area, is it a comfort having extra pairs of eyes around?

Marty says security isn’t really an issue, visitors or no.

“Touch wood, we’re lucky we live in the community we do. We’ve never had any problems. In other areas, you might worry people would see what was lying around and come back and help themselves. But not here.”

Marty has no hesitation recommending to other farmers that they consider sharing their farms’ attractions with the public.

“I just enjoy it. I find they’re always really genuine people.”

But he does have some advice.

“The biggest thing is you can’t just have open slather. They have to ring me up, make a time, meet me, sign the form.”

He says a significant pay-off for him is that he is actually sharing two treasures: the falls plus the farm itself.

“I know a lot of [farmers] couldn’t be bothered with the hassle. But I get quite a thrill out of it – some of the kids in that school group had never been on a farm, and that makes you feel quite good, actually. Show the other half what it’s like. Because farming, on the news and that, it doesn’t get a good rap, at times.”

He doesn’t consider he’s done anything particularly special by allowing, over the past two decades, some four thousand strangers to traipse across his land and through his business, for free.

“[The falls are] a marvellous site, no doubt about that. And if other people had it they would have done much the same. But maybe they would have not been as accommodating as us, I don’t know…

“I just think, if people are interested in looking, good on them. A lot of people just enjoy walking through the farm. It’s a day out – they get out their walking sticks and back packs, take their lunch and go down, come back, and they’ve had a good day.”

This article is in partnership with Herenga ā Nuku Aotearoa, the Outdoor Access Commission.

A visitor close to the base of Mangatiti Falls.

A visitor sitting on a rock beside the pool at the base of Mangatiti Falls.