Nicholas Jolly, B+LNZ's Trade Policy Advisor discusses New Zealand’s red meat trade history leading up to where we are now.

With this blog, I thought it would be worth stepping back and looking at a brief history of New Zealand’s red meat trade and where it is now. In a later blog, I will look at some of the possibilities for the future.

Early beginnings of the New Zealand red meat trade

New Zealand’s red meat trade really began in 1882, with the first shipment of frozen meat to the United Kingdom (UK). The commercial application of refrigeration technology opened up significant opportunities for sheep farmers, who had previously relied on wool for income because it could easily be transported long distances. Meat trade before 1882 was mainly domestic, with a small amount exported in cans or an otherwise preserved form.

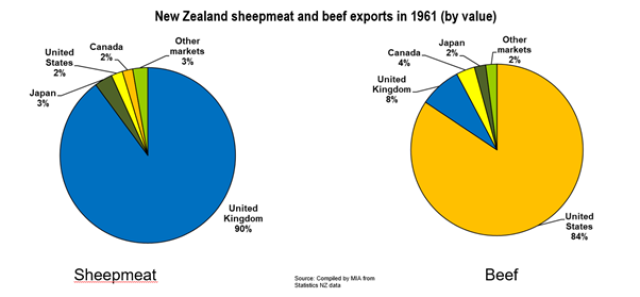

The red meat trade until the 1920’s was mainly frozen carcasses to Britain, where it was sold to butchers who further broke down the carcasses in their shops. In 1926, the first shipment of beef, mutton and lamb was sent to the United States of America (USA) and Canada, opening up new markets. This was the foundation for New Zealand’s red meat exports for the next 40 years, with sheepmeat mostly exported to the UK and beef exported to the USA.

During the Second World War, New Zealand’s reliance on these two markets increased due to an agreement signed with the UK to supply as much as possible to them to help out with war related food shortages. In 1952, this was extended to a 15-year agreement giving unlimited access to the UK market.

In the 1960’s, it became clear that the UK was going to join the European Union (EU) and exports would be limited by European trade policy through tariffs and quotas. New Zealand then attempted to find new markets, with the Meat Board establishing offices in Japan and the United States in the 1960’s, followed by offices in Brussels and Tehran (Iran) in the 1970’s. The chart above demonstrates the reliance that New Zealand had on only a few markets during this period.

Following the UK joining the EU (or European Community as it was then known), a sheepmeat quota of 245,000 tonnes was introduced with an in-quota tariff* of 10 percent, which was then subsequently reduced to 0 percent in 1989 in return for New Zealand agreeing to limit the amount of sheepmeat exported to the EU to 205,000 tonnes. This was subsequently increased to 225,000 tonnes during the Uruguay Round of negotiations which resulted in the formation of the World Trade Organisation (WTO). The formation of the WTO was an important chapter in the history of our agricultural exports as it locked tariffs at current levels and committed countries to progressively reducing them.

While agricultural tariffs have not reduced significantly for agricultural products as a result of WTO negotiations since then, this has provided security for exporters because they cannot rise above the locked in levels.

Where we are now – New Zealand’s current trade policy

In the early 2000’s, New Zealand embarked on a new trade policy of signing Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) with our major trading partners. We now have Free Trade Agreements with Australia (CER 1983), Singapore (2001), Thailand (2005), Singapore, Chile and Brunei (P4 2006), China (2008), Malaysia (2010), Hong Kong (2011), Myanmar, Laos, Vietnam, Cambodia, Philippines, and Indonesia (AANZFTA 2012), South Korea (2015), and Japan, Mexico, Peru, and Canada (CPTPP 2018).

Note that this is just a list of when we signed FTAs with new markets, as some countries we have multiple FTAs with, for example we are in multiple agreements with Australia such as the CER, AANZFTA and CPTPP.

We are currently in the process of negotiating new FTAs with the UK and the EU, which will further increase our network.

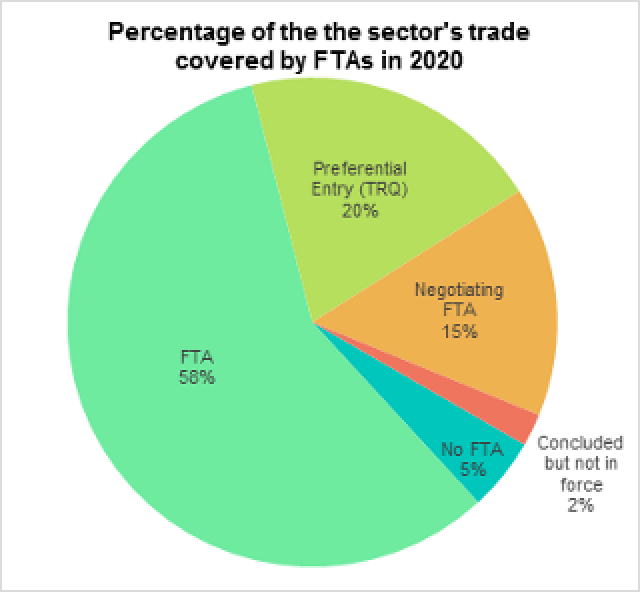

The below pie graph shows what percentage of New Zealand red meat exports are currently covered by FTAs. “Preferential entry” relates to where we have access to a market through other means, such as quotas agreed at the formation of the WTO. We currently have quotas with the United States, Canada, Europe, and the UK.

The UK and the EU are covered by the ‘Negotiating FTA’ segment as negotiations are ongoing.

It is also important to note that even if we have a FTA with a market, that does not necessarily mean tariffs are at zero, for example with South Korea tariffs are reducing from 40 percent to zero over 14 years. They are currently at 21.3 percent.

The “Concluded but not in force” segment refers to the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), made up of Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, Qatar, Kuwait, Oman, and Bahrain. Negotiations concluded in 2009, with increased access for red meat exports but the FTA has since stalled. Current regional dynamics have also impacted on the ability of GCC states to take a collective decision. As a result, the FTA is unlikely to be completed until this deadlock is resolved.

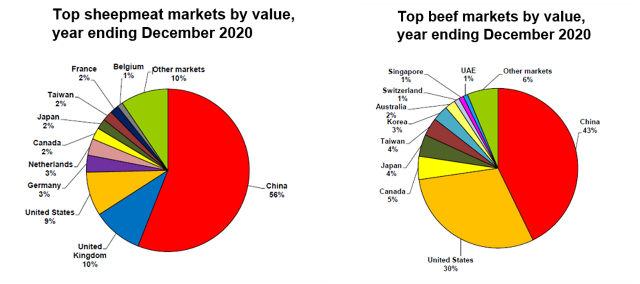

The below charts, put together by the Meat Industry Association show how our trade has diversified since the 1960’s. While a significant percentage of exports are destined for China, we have a network of FTA’s that mean if something happens to China, our exporters have other options. We saw this when the COVID-19 outbreak first started, as when Chinese ports were closed exporters were able to redirect product originally destined for China to other markets. In 2020, the sector exported over $9.52 billion worth of product, the highest level ever.

This demonstrates that our trade strategy of having a large network of FTAs is working. It provides resilience in times of crisis, while returning value as exporters can match cuts to demand, therefore providing maximum value from each carcase and returning this to farmers pockets.